Marriage is often seen as the ultimate romantic commitment, a beautiful union of two people who share not only love but also hopes, dreams, and…

Table of Contents

The Domestic Violence QLD Act is Handled by a Brisbane Domestic Violence Lawyer

What is domestic violence?

While domestic violence can look differently for each family, it often includes a pattern of behaviours intended to control or generate fear by one person (the perpetrator or respondent) against another (the victim or aggrieved). This behaviour can manifest in ways that are physical or non-physical.

The different forms of abuse can look like:

- Physical abuse to a person: hitting, punching, shoving slapping, choking, using or pointing weapon;

- Physical damage to property;

- Psychological abuse such as emotional or verbal abuse, insults, offensive language and constant put-downs;

- Social abuse such as preventing the victim from leaving the home, deliberate geographical isolation, controlling the use of the phone and restricting contact with family and friends;

- Financial abuse such as restricting access to money or providing insufficient funds for necessities;

- Sexual abuse such as non-consensual intercourse or sexual acts, including child sexual abuse where a parent or care giver involves a child in sexual activity;

- Technology-facilitated abuse such as threatening or insulting text messages; or

- Spiritual abuse such as not allowing a person to practise their religious or cultural beliefs.[1]

It is important to acknowledge that coercive control falls under the umbrella of domestic violence and describes a pattern of behaviours aimed at controlling an intimate partner and/or family members.[2] The effects of coercive control can be devastating and can include the loss of the victim’s autonomy, freedom and sense of trust for others.[3]

If you have experienced any of the above behaviours –

If you have experienced any of the above, we strongly advise that you contact the police or seek legal help as soon as possible. From there, it is likely that a protection order can be made by the Magistrates Court to protect you and your loved ones.

By successfully applying for a domestic violence order, the courts can enforce such an order to ensure that the respondent is legally bound to refrain from conducting any of the behaviours listed above against the aggrieved or a named person.

What is a domestic violence order?

Under the Domestic and Family Violence Protection Act 2012 (Qld) (‘the DFVP Act’), a domestic violence order is a protection order made by the court to try and stop threats or acts of domestic violence against the person experiencing the abuse. The central principles that guide the court when making a protection order include the safety, protection and wellbeing of people who fear or experience domestic violence, including children.[4] The court refers to this class of people as the ‘aggrieved’.

Who can apply for a protection order?

The following classes of people can apply for a protection order:[5]

- The aggrieved (the person who has experienced the DV);

- A person who is authorised by the aggrieved to apply for an order, such as a domestic violence service worker; or

- A police officer.[6]

If the police are called to a home or location where they believe that domestic violence has occurred, the police can apply for an order to protection you and your loved ones.

Also note that a person under 18 can be either an applicant or respondent to a protection order if they are in an intimate personal relationship or an informal care relationship, but not a family relationship.[7] Referrals to other agencies, including Family and Child Connect, a Family Wellbeing Service or Child Safety should be considered whereby the child is unable to apply for a DV order against their parents or other family members. Useful information can be found via: Department of Child Safety, Seniors and Disability Services (dcssds.qld.gov.au)

How to apply for a protection order –

Step 1: fill in the From DV1

An application for a protection order (Form DV1) can be located from the local Magistrates Court, police station or online from the website: https://www.courts.qld.gov.au/going-to-court/domestic-violence.

Make sure the statutory declaration is signed front of a Justice of the Peace (JP) or Commissioner for Declarations (CDec). Most Magistrate courts have JPs available who can witness signatures.

Step 2: include as much information of the domestic violence as possible

It is helpful to the court to include as much detail as possible, which may include:

- The type of violence;

- When it happened or how often it happened;

- Where it happened;

- What happened;

- How it happened;

- Who was there; and

- Any injuries suffered.

It is important to try and attach the following documents as forms of evidence to the application:

- Photos of any injuries taken at the time the domestic violence happened;

- Photos of any injuries taken later when they are more visible;

- Statements from people who saw or heard the domestic violence or who are aware of the domestic violence over a period of time;

- Diary entries made about the domestic violence;

- Doctors’ reports;

- Other court orders, e.g. other domestic violence orders or family law orders;

- Reports from any counsellors;

- Phone call logs of calls made to a phone by the respondent; and

- All text and voicemail messages, emails, letters and social media entries (printed out with dates).

To place yourself in the position of a court, below is a summary of what factors the court considers under the DVFP Act when granting a protection order:

1. You are in a relationship covered by the DFVP Act

The relationship must fall within any of the following categories:[9]

- An intimate, personal relationship. This means a current or former spouse, a parent of a child together, an engaged couple or couples who are living or have lived together;[10]

- A family relationship. This means that the aggrieved is related to the respondent by blood or marriage;[11] or

- An informal care relationship. This can exist where one person is dependent on the other person for aspects of daily living but not applicable whereby the carer is paid (excluding government payments) by the applicant.[12]

2. Domestic violence has occurred

Domestic violence means behaviour that:[14]

- Is physically or sexually abusive;

- Is emotionally or psychologically abusive;

- Is economically abusive; or

- Is threatening;

- Is coercive; or

- In any other way controls or dominates the aggrieved and causes the aggrieved to fear for their safety or wellbeing or that of someone else.

The behaviours listed above:

- May occur over a period of time;

- May be more than 1 act, or a series of acts, that when considered cumulatively, constitutes DV; and

- Is to be considered in the context of the relationship as a whole.[15]

Note that a person who counsels or encourages someone else to engage in the above behaviour that is regarded to have engaged in domestic violence.[16]

- The protection order is necessary or desirable to protect the aggrieved from domestic violence

Here, the court will look at the need for protection against the risk of future domestic violence, provided that the DV is real and continuing.

This assessment will depend on the particular facts of the case. The court will examine factors such as:

- Evidence of past domestic violence and conduct;

- Genuine remorse of the respondent;

- Rehabilitation including counselling;

- Medical treatment;

- Compliance with any temporary protection orders; and

- Changes of circumstances (such as parties separating or one party relocating to another place).

These three conditions must all be satisfied for the court to make a DV order.

More information can be found by visiting:

DV – Guide to completing an application for a protection order (courts.qld.gov.au)

Step 3: file the application for the protection order at the Magistrates Court

An application must be in the official form (DV1) and should be filed in a Magistrates Court.[18] The aggrieved or the aggrieved’s solicitor can file the application. It can also be filed via post. In some rare circumstances, the application can be filed via email. Learn more about electronically filing an application by visiting: Electronically filed domestic and family violence documents | Queensland Courts.

There is no filing fee attached to this process.

Step 4: serving the sealed application

Once the application is filed, a date for the hearing of the application will be provided immediately.[19] The clerk of the court will arrange for the police to serve (deliver) a copy of the application and any temporary order on the respondent.

The nearest police station can also inform the aggrieved on whether the application has been served on the respondent. Even if the application has not been served, the aggrieved will still have to go to court.

The respondent will receive a copy of the full application and attachments. If the aggrieved wishes to keep the address on the application form private from the respondent, the following form needs to be filed along with the DV order application: Form DV0IC – Aggrieved details form (version 2 – published on 17 July 2023) (courts.qld.gov.au)

If there are concerns about immediate safety, the aggrieved can ask the court to consider making an urgent ‘temporary protection order’. If the circumstances are urgent, the DV order application can be quickly listed to go before a magistrate. This can happen even if the application has not yet been served on the respondent. Make sure the box for a temporary protection order is ticked.

Step 5: carefully read the conditions of the order once it has been made

When making an order, the court has wide discretion, and an order could prevent the respondent from:

- Approaching the aggrieved or a named person at a home or workplace;

- Staying in a home the respondent and aggrieved used to share;

- Approaching another person, relatives or their friends, if named in the order, within a certain distance;

- Going to a named child’s school or place of education/childcare; or

- Breaching the court order.

On top of these restrictions, there are certain conditions that must be included in all protection orders. These ‘standard conditions’ require the respondent to:

- be of good behaviour to the aggrieved and any named persons;

- not commit domestic towards the aggrieved or any named persons; and

- if a child is named, not expose the child to any forms of domestic violence.[20]

An order can continue for any period of time that the court thinks is necessary. If the time period is not expressly stated in the order, the period will continue for five years from when the order is made, however the court has discretion here.[21]

A protection order can protect both the aggrieved and other people who have been affected by the violence. A person included on the order is called a ‘named person’ and the conditions that apply to protect the aggrieved will apply to the named person. People who can be named and protected on the order include:

- A child;

- A child who usually lives or spends time with the aggrived on a regular basis;

- A relative of the aggrieved; and

- An associated person of the aggrieved, such as a new partner, colleague or friend.[22]

Note that the court is required to consider naming a child or children on a protection order[23] even if the parties have not requested that the child or children be named, or if the respondent does not provide consent.

What different types of orders are there?

The court can make different types of orders based on the circumstances of the case, and these orders include:

| Order type | Purpose and effects |

| Final protection orders

| This order is made once a final decision by the court has been made. The court may make a protection order against the respondent if the court is satisfied that:[24]

|

| Temporary protection orders | This ordder is made while a court decides whether to make a final protection order. It must be satisfied that there is a relevant relationship and that the respondent has committed domestic violence.[26] Here, to prove that the respondent engaged in domestic violence, the standard of evidence needs to only be sufficient and appropriate (the standard of evidence is lower compared to a final order).[27] |

| Urgent orders | Also known as an ex parte order, this order aims to protect the aggrieved even if the respondent is not present in court or has not been notified about an application for a domestic violence order.[28] These orders will be made whereby the serious nature of the allegations warrant an order being made prior to the respondent being served and notified. |

| Consent orders | This order results in consent from the respondent without admission. [29] For the court to make a consent order, a relevant relationship must exist between the aggrieved and the respondent.[30] Here, the court does not need to be satisfied that domestic violence has occurred.[31] |

| Intervention orders | The court can make this order when the court is also making or varying a domestic violence order. This type of order requires the respondent to attend counselling or an approved intervention program to address their violent behaviour.[32] This order requires the respondent’s consent.[33] A list of appropriate programs can be found by visiting: Find local support | Community support | Queensland Government (www.qld.gov.au) |

| Police protection notices (PPN) | If the police visit a location where they believe that domestic violence has occurred and an order is urgently necessary, they can issue a PNN on the spot to protect the aggrieved and/or any named person immediately from further violence. It has the same effect as a domestic violence order until the matter is heard in court. If the named person is a child, then the respondent must not expose the child to any forms of violence. If the attending officers believe it is necessary and reasonable, PPNs can require the respondent to:

Once a PPN is made, a copy of the notice will be filed by an officer at the local Magistrates Court and then served upon the respondent. This PPN will be regarded as an application for a protection order made by a police officer. The PPN will remain in force until the order is served on the respondent.[38] If a PPN is breached by the respondent, the maximum penalty is three years imprisonment or 120 penalty units ($137.85 per unit as of 1 July 2021).[39] |

Can the protection order be appealed?

If either party disagrees with the magistrate’s decision, it can be appealed. The appeal needs to be filed in the District Court within 28 days from the date the magistrate made the decision about the protection order.

Can the protection order affect any existing family law orders?

The court must consider any existing family law or child protection orders before deciding to make or change a protection order. Either party must tell the court of any existing family law or child protection orders, attach a copy of the orders to the protection order application or give a copy to the court.

The court must consider changing the family law order if the conditions in the order:

- conflict with conditions in the protection order; and

- could make the aggrieved, any children or anyone else named in the domestic violence application unsafe.

What happens after the domestic violence application is filed with the Court?

| Court phase | What to expect |

| Attending the mention | After the application for a protection order has been filed there may be some short court appearances before the application can be finalised. These short appearances are called ‘mentions’. The first mention will likely take place 3-4 weeks after the application is filed at court. The aggrieved will be provided with the first court date when the application is filed at the Magistrates Court. On the first court date, the magistrate will want to know if the respondent has been served by the police, if they are present in court and whether they agree or disagree with a domestic violence order being made. |

| Both parties agree on the order | If parties attend court and agree to the order, then the court can make a final protection order.[40] |

| Respondent does not agree to the order | If the respondent does not agree to the order, the matter may be sat down at a later date for a contested hearing (trial), and a temporary order will be made. More information about what happens at a trial can be access via: What happens at a contested hearing? |

| Respondent does not receive the application and does not attend court | If the respondent is not present and has not yet been served with a copy of the application, the court may adjourn the case and make another date for the mention. Here, the court can make a temporary order that is enforceable until a final decision is made. This aims to protect the aggrieved or named parties in the meantime. |

| Respondent receives the application, but does not attend court | If the respondent is not present at the mention but has been served with the application, then the court may make a final DV order.[41] |

Non-compliance with the protection order

Only the police can charge the respondent with breaching the protection order, and this can constitute a criminal offence. If the aggrieved believes that the order has been breached, the details of the breach ought to be recorded immediately as this may help the police. It will also help the police if there is evidence of the breach in the forms of:

- Text messages;

- Posts on social media sites;

- Letters;

- Photographs;

- Phone messages; and

- Any diary entries.

If the aggrieved informs the police that the respondent has breached the protection order, they must investigate and may charge the respondent with breaching the order.

It will be a criminal offence if the respondent fails to comply with the protection order.[42] If the respondent has been previously convicted of an offence (breach of an order) within the past 5 years, the penalty will be 5 years imprisonment or 240 penalty units ($33,084). If the respondent has not been convicted of a previous breach, but has breached your current order, the penalty will be 3 years imprisonment or 120 penalty units ($16,554).

The rights of the aggrieved in Court

The aggrieved may bring a support person during the hearing, however they are not permitted speak on the aggrieved’s behalf unless authorised to do so.

Court staff can arrange additional safety precautions for the aggrieved, such as waiting in a safety room rather than in a public area. A safety form ought to be completed here and this can be resourced by approaching a court officer.

The court will consider whether to make the aggrieved, a child or a relative/associate a ‘protected person’ in the proceedings. This can allow the protected person to provide evidence in a way that is less confronting than standing in a court room and being asked questions by the person they allege has caused them harm. For instance, evidence can be provided outside the court room via an audio-visual link, a screen or one-way glass can be placed so that the protected person cannot see the respondent or the respondent could be required to stay in another room while the protected person gives evidence. The court will be closed to the public.[43]

If a party wishes attend a court event by telephone or audio-visual link rather than in person due to safety reasons or personal responsibilities, court approval must be granted. A form must be completed (DV01F) and filed with the protection order application. Alternatively, an email can be sent to the Magistrates court requesting to appear remotely. E-mail contact details for each courthouse can be found at https://www.courts.qld.gov.au/contacts/courthouses

A magistrate will consider a request to appear remotely and court registry staff will advise the aggrieved before the court date whether the request is granted. If the aggrieved does not hear from the court registry about the request to appear remotely, the aggrieved must attend court in person

Support – legal assistance

Both parties have the right to receive legal help and assistance. The parties can represent themselves or engage a lawyer to appear for them. The following table outlines the different avenues of assistance offered by the court.

| Who can help?

| How? |

Police prosecutor | A police prosecutor can represent the aggrieved where police are making the application for a protetcion order on the aggrieved’s behalf, such as when the police file a PPN. A police prosecutor can also appear for an aggrieved who is making their own application. Here, the aggrieved should approach the police prosecutor in court and ask for assistance. |

Lawyer | Legal assistance for both parties can be obtained via Legal Aid Queensland if the party is eligible for a grant of aid. Community legal centres may also be able to assist in completing the application form for a protection order. Otherwise, a private solicitor may also be engaged at either parties’ expense. |

Domestic violence duty lawyer | A domestic violence duty lawyer is a free lawyer available in 14 courts across Queensland. This type of lawyer can provide legal advice throughout the process and sometimes on the day of court to either party. A domestic violence duty lawyer does not need to be booked in advance, but availability should always be checked by visiting: Domestic and family violence duty lawyer – Legal Aid Queensland Alternatively, inquiries can be made to Legal Aid Queensland on 1300 267 762. |

| Women’s Legal Service

| Women’s Legal Service operates a domestic violence unit in Brisbane, on the Gold Coast and in Caboolture. Here, assistance includes legal advice, safety planning, assistance to draft documents and in some cases, representation in court. Visit Get Help | Women’s Legal Service Queensland | Free legal assistance (wlsq.org.au) for more information. |

Queensland Domestic Violence Services Network | There are numerous violence prevention clinics across Queensland that can assist an aggrieved party to apply for an order, help the aggrieved access the court’s safety facilities, explain orders, assist with applications, liaise with the police prosecutor and refer the aggrieved to legal advice or representation. Visit Services – QDVSN – Queensland Domestic Violence Services Network for more information. |

| Victim Assist Queensland | Victim Assist Queensland is a unit of the Department of Justice & Attorney-General responsible for providing information, referrals to support and financial assistance to victims of violent crime. If the aggrieved has been injured in an act of personal violence, including acts of domestic or family violence, Victim Assist may be able to refund money spent, or cover the cost of:

To contact Victim Assist for more information, call 1300 546 587, visit www.qld.gov.au/victims or email victimassist@justice.qld.gov.au |

How much will this whole process cost?

If the services of a private lawyer have been engaged, these costs are incurred by the party. There are no costs if a police prosecutor represents the aggrieved at court. The aggrieved can apply for a Legal Aid Queensland lawyer if the police prosecutor is not available—depending on financial circumstances, the party may have to make a contribution towards legal aid costs.

The magistrate may make the aggrieved pay the respondent’s court costs if they decide to dismiss the application because they believe it is deliberately false, frivolous, vexatious or malicious.

Useful contacts

Legal services

- Legal Aid Queensland – 1300 65 11 88

- Community Legal Centres Queensland – (07) 3392 0092

- Indigenous Hotline (Legal Aid Queensland) – 1300 65 01 43

- Violence Prevention and Women’s Advocacy (Legal Aid Queensland) – (07) 3917 0597

- Queensland Indigenous Family Violence Legal Service – 1800 887 700

- Women’s Legal Service – 1800 957 957

- Women’s Legal Service – Rural, Regional and Remote Line – 1800 457 117

- Refugee and Immigration Legal Service – (07) 3846 9333

- LGBTI Legal Service – (07) 3124 7160

- Queensland Law Society –1300 367 757

- Aged and Disability Advocacy Australia –1800 818 338

Government agencies

- Women’s Infolink –1800 177 577

- Centrelink –13 28 50

- Child Safety Enquiries and Notification Unit –1800 811 810

Domestic violence services

- 1800 RESPECT telephone counselling –1800 737 732

- DV Connect –1800 811 81

- DV Connect, Mensline –1800 600 636

- Mensline Australia – 1300 789 978

- Immigrant Women’s Support Service – (07) 3846 3490

Counselling and support services

- Lifeline – 13 11 14

- Suicide Call Back Service –1300 659 467

- Ozcare –1800 692 273

- Relationships Australia and Rainbow Counselling –1300 364 277

- Diverse Voices (LGBTI peer support) –1800 184 527

Interpreting services

- Deaf Services Queensland – (07) 3892 8500

- National Relay Service –1300 65 11 88

- Translating and Interpreting Service –13 14 50

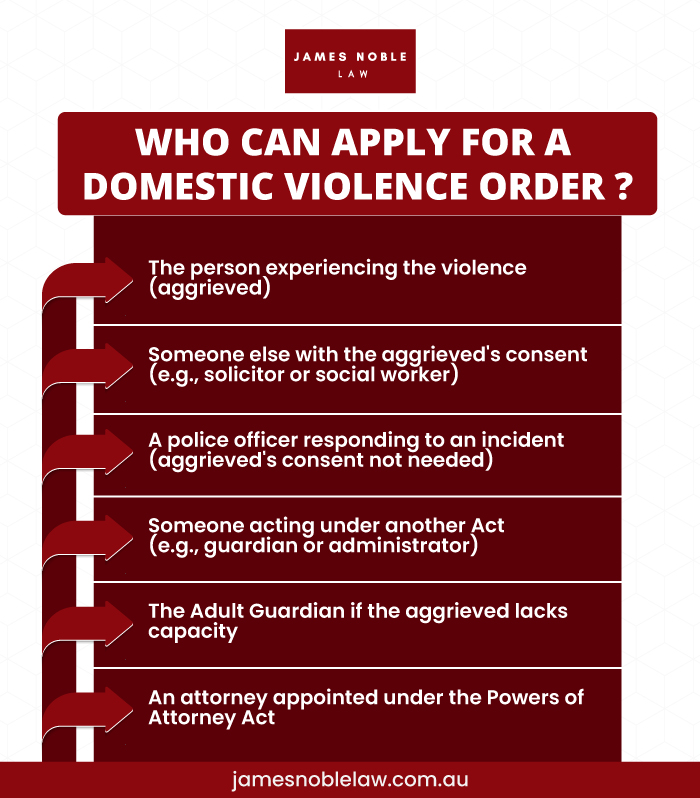

Who can apply to the court for domestic violence?

Who can apply to the court for domestic violence? the person experiencing the domestic and family violence (the aggrieved)

- someone else, for example, a solicitor or social worker, can apply on behalf of the aggrieved with the aggrieved person’s consent

- a police officer attending a call out due to an incident of domestic and family violence. The consent of the aggrieved is not required for a police application

- someone acting under another Act for the aggrieved, for example, a guardian for a personal matter, or an administrator for a financial matter under the Guardianship and Administration Act 2000

- the Adult Guardian can apply if they believe that the aggrieved needs legal protection but does not have the capacity to apply for a protection order

- someone who is appointed as the attorney of the aggrieved under the Powers of Attorney Act 1998 and who makes the application under the enduring power of attorney QLD.

Orders can be issued by the Court on a temporary or permanent nature. The general order made by the Court is:

- The respondent (the person who uses abuse or violence) must be of good behaviour towards the aggrieved (the person who needs the order to protect them) and not commit domestic violence

- If a named person is specified in the order the respondent must be of good behaviour towards the named person and not commit an act of associated domestic violence against the person.

Other orders can be made by the Court confiscating firearms, removing a party from the family home, limiting the powers of a party to contact the person affected by the domestic violence including children and orders prohibiting a party from being in the vicinity of the family home, the workplace of the other party or contacting the party by any means.

What are the police powers in relation to this?

The role of the Queensland Police is to respond to threats or incidences of violence and bring the matter before the Court. Many police officers are called to domestic violence incidents by victims or concerned neighbours.

The priority of a police officer called to an incident is to ensure the safety of the parties involved.

A Queensland Police publication advises that:

If a police officer reasonably suspects an incident of violence(including physical, sexual, verbal or financial abuse; damage to property; harassment or intimidation; or threatening to do any of these), it is their duty to investigate the matter thoroughly.

This investigation may include:

Separating the parties

- Asking personal questions — such as the history of the relationship and the reason for the present problem.

- Searching the premises for anything associated with causing injury or harm.

- Removing the person using domestic violence and placing them in custody for up to four hours.

Can I make my own domestic violence application?

If the police are not willing to act and initiate an application for a Protection Order a person may apply for one or have their lawyer bring the domestic violence application on their behalf.

If a lawyer assists, they can draft the necessary application ensuring that it contains all relevant information that the Court will require to consider that application. The lawyer can represent the party in all aspects of the application and the subsequent hearings in the Court.

At James Noble Law we have the knowledge and experience to advise and guide our clients through the many and varied intricacies associated with domestic violence proceedings.

We will draft the necessary documents to ensure they set out all relevant circumstances to comply with the legislative requirements to achieve the best outcome and to represent our clients in domestic violence court proceedings. We are only too happy to act on your behalf in this regard.

In need of legal support?

At James Noble Law, we are here to support and help you through this difficult process. We are your trusted Family Law experts, offering Family Law Services in Brisbane, Cairns Family Law, and Milton Family law Services for more than 50 years. Speak to one of our lawyers to better understand your rights. We offer a complimentary 20-minute consultation with our skilled legal team – no strings attached. Secure your appointment now to connect with our experienced family lawyers.

Call our team on 07 2112 3947 or email us at team@jamesnoblelaw.com.au.

Explore:

🌟 Accomplished Brisbane Family Lawyers. 🌟 Devoted Cairns Family Lawyers. 🌟 Proficient Milton Family Lawyers.

Easily locate us on Google Maps and take the proactive step towards resolving your legal matters. Seize this opportunity for guidance from our seasoned professionals. Act today and pave the way for legal clarity and confidence!

You may also like to know more information about the

NEED HELP?

TALK TO A NOBLE FAMILY LAWYER

FAMILY LAW NEWS

Keep up to date and receive clarity on a range of news related articles on the James Noble Law blog.

By James Noble Law, Queensland Family Law Experts When it comes to parenting arrangements after separation or divorce, one of the most common questions we…

When entering a relationship or going through a separation, financial security and clarity are paramount. That’s where a Binding Financial Agreement (BFA) may be advisable.…